Do Longer Games Lead to Better Chess? A Data Science Investigation

The Hypothesis: Memorization vs. Deep Learning

In the chess world, there’s a long-standing debate about improvement. Bobby Fischer famously complained that chess was becoming “all about memorization.” With modern engines, players can memorize opening lines 30 moves deep. My hypothesis was simple: players who rely on memorization (shorter games) improve less than players who fight through complex positions (longer games).

In cognitive science terms, this is “Rote Learning” vs. “Meaningful Learning.” I set out to test this using the massive Lichess open database.

Big Data Pipeline

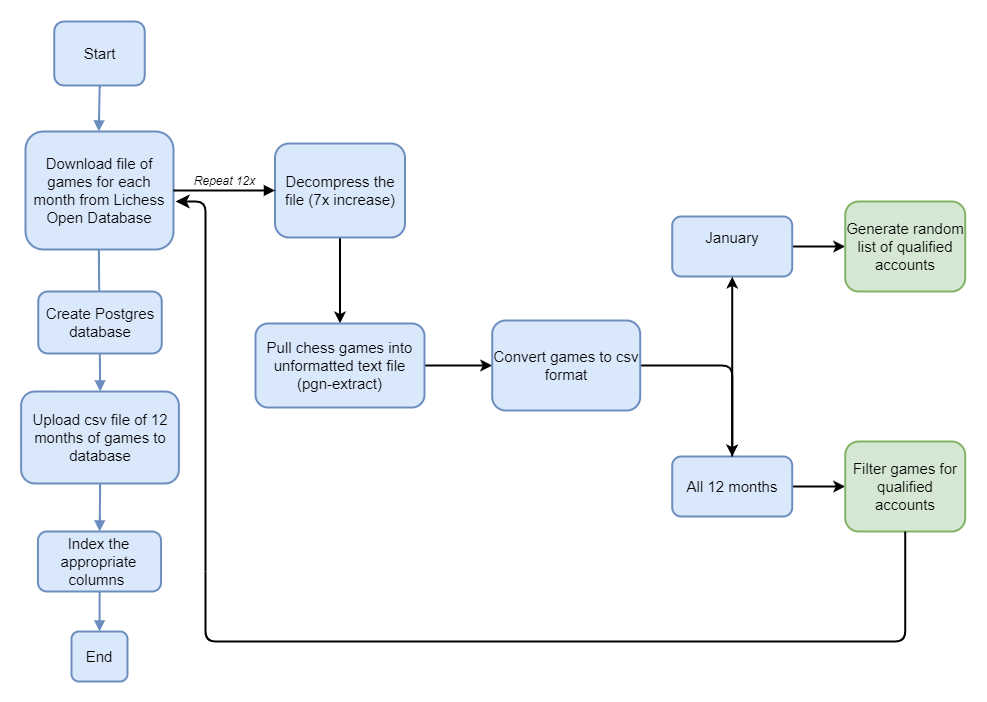

To test this, I needed data—a lot of it. The Lichess dataset is enormous, with billions of games.

1. Ingestion & Parsing

The raw data consisted of 12 months of PGN files, totaling about 2.5 TB uncompressed. Python was too slow for parsing this volume of text, so I used pgn-extract, a high-performance C CLI tool, to parse the games.

Figure 1: The data extraction pipeline from raw PGN to Postgres.

Figure 1: The data extraction pipeline from raw PGN to Postgres.

2. Sampling Strategy

I couldn’t analyze everyone. I filtered for:

- Time Control: Rapid (>10 mins) to minimize time-scramble noise.

- Population: ~130,000 unique accounts.

- Stratification: selected 10,000 accounts from each Elo bucket (800–2500) to ensure representation across skill levels.

3. Database Architecture

I loaded the processed data into PostgreSQL. The schema linked Accounts (tracking skill growth) to Games (tracking move counts and results). Indexing the account_id reduced query times from minutes to milliseconds.

Feature Engineering: Normalizing Game Length

Here lies the main data science challenge: Better players play longer games.

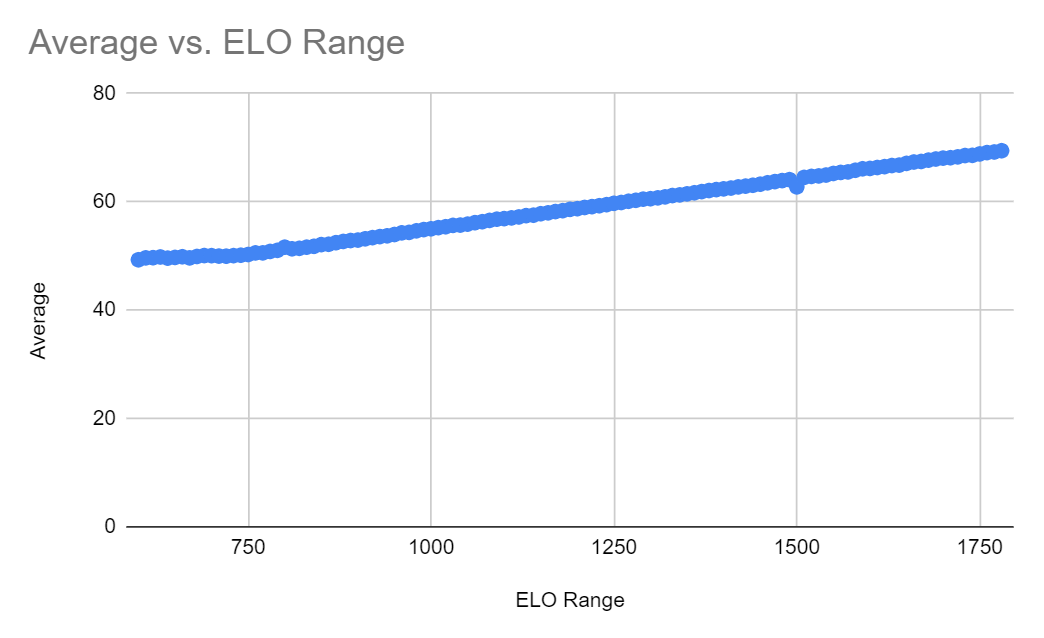

Figure 2: As Elo increases, the average game length increases.

Figure 2: As Elo increases, the average game length increases.

If I simply correlated “average game length” with “Elo growth,” I’d just be rediscovering that good players play long games. I needed a metric for Game Length Tendency that was independent of skill.

The Solution: Z-Scores

- I calculated the mean and standard deviation of game lengths for every 50-point Elo bucket.

- For every game a player played, I calculated a Z-score: how much longer/shorter was this game compared to the average game at that specific Elo?

- I averaged these Z-scores to get a single “Length Tendency” for each player.

The Analysis & Results

I used a Spearman Rank Correlation to compare:

- Length Tendency: Do you tend to play games longer than your peers?

- Skill Growth: How much did your Elo improve over the year (relative to your starting bracket)?

The Verdict

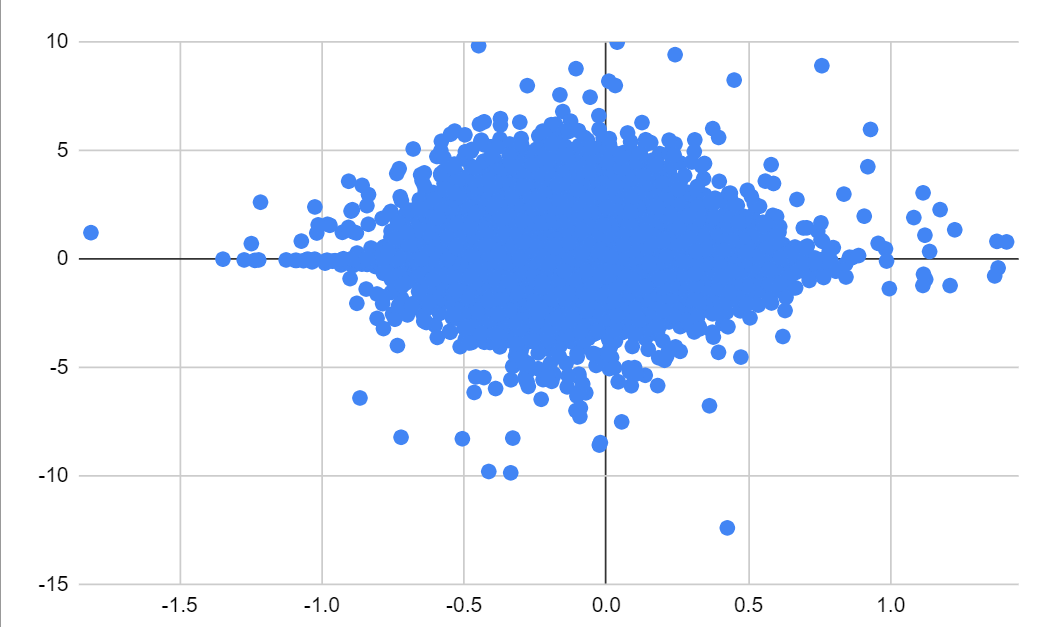

Figure 3: Game Length Tendency (x-axis) vs. Skill Improvement (y-axis).

Figure 3: Game Length Tendency (x-axis) vs. Skill Improvement (y-axis).

Correlation Coefficient: 0.0632

The result was effectively zero. There is no statistically significant correlation between playing longer games and improving faster at chess.

Conclusion & Critique

Why did the hypothesis fail?

- Metric Sensitivity: Elo is a noisy proxy for skill. Winning streaks and losing streaks (which happen frequently in online chess) cause Elo to oscillate around a player’s “true” skill, introducing significant noise.

- Matchmaking: Lichess pairs players very tightly (within ~100 Elo points). This creates a localized competitive environment where “true skill” advantages are minimized, dampening the signal.

- The Complexity of Improvement: Chess improvement is likely multi-factorial. Tactics training, analysis, and study habits likely outweigh the simple duration of games played.

While the null hypothesis stands, the infrastructure built—a 2.5TB parser and normalized metrics engine—paves the way for deeper behavioral analysis of chess players.